At the start of this week, a shocking screenshot went viral in investment circles on the X platform, spreading at a rate of hundreds per hour. Its alarming claims included information about a "systemically important" bank. Silver market crashes and near-bankruptcy, forced liquidations by exchanges late at night, and the Federal Reserve reportedly forced to inject billions of dollars into the system—all these events are triggering every sensitive nerve in the financial world.

This reads like a sequel to the movies *The Big Short* or *Margin Call*, and during the traditionally slow news season between Christmas and New Year's, the entire internet is buzzing about it. The bank whose name has been "omitted" has sparked countless speculations within the industry, from JPMorgan Chase... UBS – the list of victims of “ bank liquidation” is endless.

However, as a tried-and-true axiom in daily life goes, "The most captivating content is often the most dishonest" —rumors stop with the wise, and debunking rumors comes from action. When we carefully examine those seemingly "boring" documents, it's actually quite easy to distinguish truth from falsehood. Because if such a significant event had truly occurred, it would certainly be reflected there…

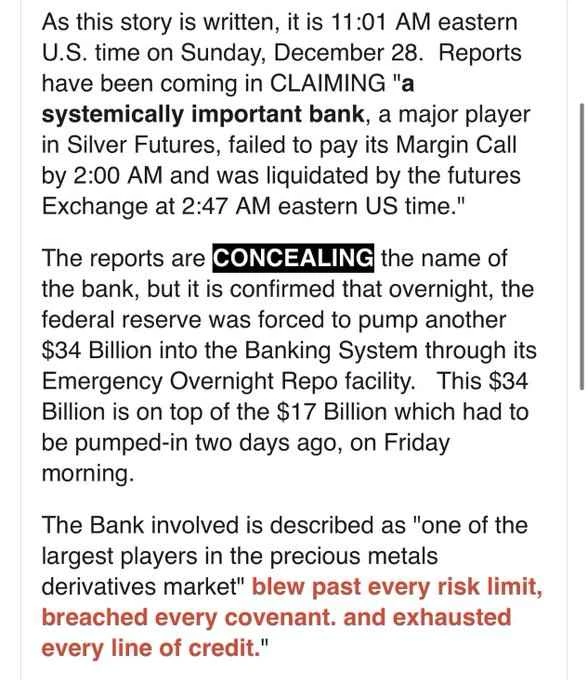

Let's first look at what the rumors that started last weekend actually said:

According to a version widely circulated on the social media platform X, the "story" "began" on Sunday: a systemically important bank—a major player in the Comex silver futures market—failed to pay margin calls by 2 a.m. ET on Sunday and was forced to liquidate by the futures exchange at 2:47 a.m. ET.

The report omitted the names of the banks but added that reliable sources indicated that the Federal Reserve was forced to inject $34 billion into the banking system overnight through an emergency overnight repurchase mechanism, in addition to the $17 billion injected last Friday.

The bank was also described as " precious metals" . "One of the biggest players in the derivatives market" has breached all risk limits, violated every contract, and exhausted every credit line.

Interestingly, upon closer examination, the reason this rumor has spread so widely may lie in its being "half true and half false."

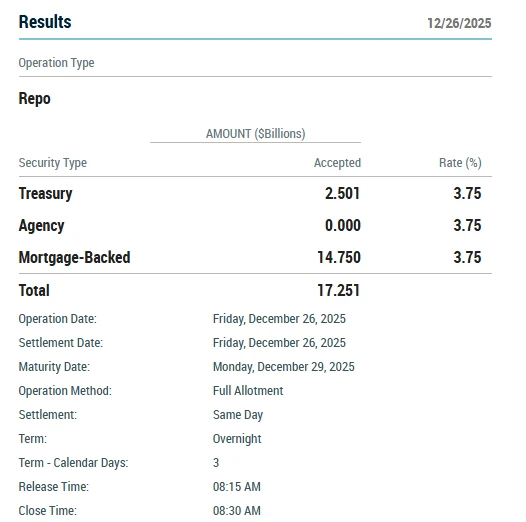

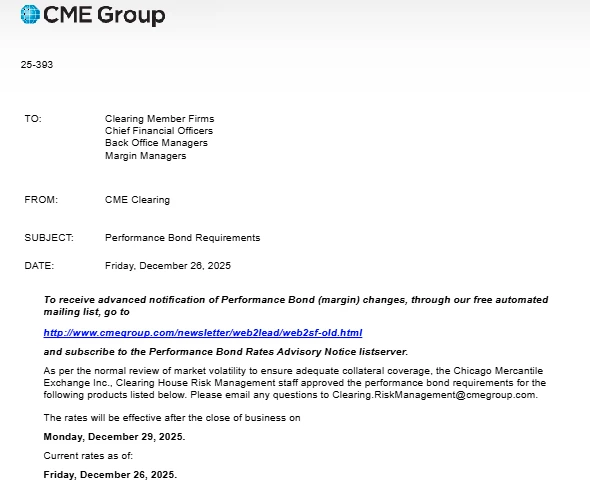

There are, of course, some "truths" in the rumors. For example, the Federal Reserve does indeed operate a repurchase agreement (repo) mechanism with the banking system—and last Friday, the Fed did inject $17.25 billion into the banking system through overnight repos. This information can be clearly found on the New York Fed's website.

However, the rumored injection of $34 billion into the banking system by the Federal Reserve through an emergency overnight repurchase agreement is "unverifiable"—as of Monday, the New York Fed had still not made any statement on the matter. Information available on its official website shows that Monday's overnight repurchase agreement utilized $25.9 billion. The $17.25 billion operation last Friday occurred entirely in the morning, with zero demand in the afternoon (making it almost entirely unrelated to the silver market).

In fact, considering that the year is approaching and there is traditionally seasonal liquidity pressure, the repurchase operations of $17.25 billion and $25.9 billion over two consecutive trading days are within a reasonable range. As we can see from the chart above, the usage of the repurchase mechanism was far greater at the end of October when the US "cash crunch" was at its worst. Therefore, hastily linking the usage of these conventional mechanisms with the so-called "bank silver margin calls" is undoubtedly far-fetched.

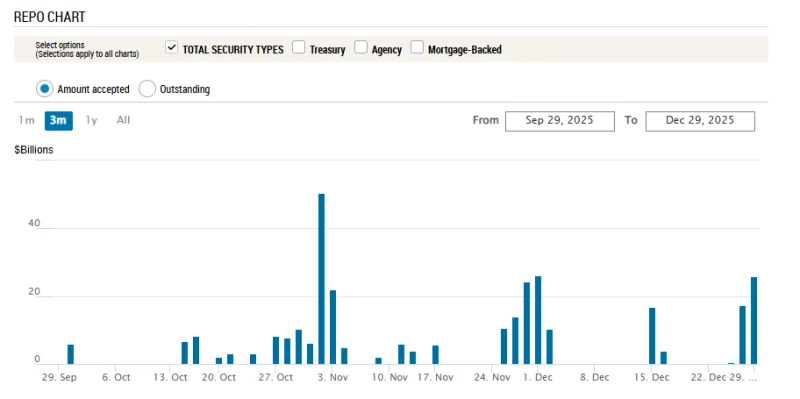

Another part of this story that is half true and half false is undoubtedly the margin call and forced liquidation that banks faced.

Last Friday, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange The CME did indeed announce a second increase in margin requirements for silver trading within two weeks, with the new rules taking effect on December 29. However, if a large clearing member fails to meet the CME's margin call requirements and is liquidated by the clearinghouse, then even if it appears somewhat ambiguous from the outside, there will be many things that must be made public.

The CME Clearing House is a systemically important derivatives clearing house and an infrastructure closely monitored by regulators. As stated in a report to the CFTC (Commodity Futures Trading Commission) on CME Clearing practices, its mechanisms are built around formal risk control, stress testing, and default management processes. This doesn't mean every detail will make headlines, but it does mean that stories of "midnight liquidation" must be examined within a comprehensive framework of compliance, reporting, and operational procedures.

In short, if a well-known bank were to suffer a margin call in silver futures trading, the situation would not be limited to a single screenshot and a few viral posts.

Currently, we have been unable to find evidence in any place where such news would typically appear, nor have we found any reliable original reports that match the claim—no CME Group member default notices, no statements from regulatory agencies, and no reports from major news agencies.

Interestingly, there were actually different versions of the aforementioned "short essays" before and after their rise and spread.

The first tragic "bank liquidation" to be publicized was Wall Street giant JPMorgan Chase , due to its past record of manipulating silver prices and maliciously shorting precious metals. In September 2020, JPMorgan Chase agreed to pay $920 million to settle its U.S. securities... The Federal Reserve (SEC), the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), and the Department of Justice (DOJ) are conducting a federal investigation into his manipulation of the precious metals and U.S. Treasury futures markets. This effectively means that JPMorgan Chase traders heavily relied on the paper silver market, futures, and ETF trading to manipulate prices. They successfully drove down silver prices by placing large sell orders that never involved physical silver transactions, without handling almost any physical silver.

Judging from media reports and social media information over the past month, similar claims about JPMorgan Chase "closing out short positions in silver" actually appeared as early as the beginning of December—and there were still believers in the public until last week.

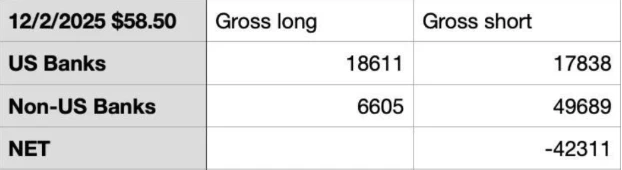

Interestingly, if one examines the CFTC's Commitment of Traders (COT) reports (which categorize banks by US and non-US), it's easy to see that, according to the monthly survey conducted in early December, major US banks, represented by JPMorgan Chase, are currently net long positions in the silver futures market. Meanwhile, it is non-US banks that are truly holding a large number of short positions—49,689 short contracts.

Thus, a second version of the short essay titled "Banks Facing Liquidation" emerged—UBS (Credit Suisse's "corpse is barely cold," is this an attempt to wipe out the entire Swiss banking system?)...

However, there are still some underlying factors that are not "easily" plausible...

For example, the CFTC's comprehensive report on COMEX silver futures and options shows that as of December 16, the total open interest was approximately 224,867 contracts, a figure publicly available in the report. If we assume an additional $3,000 per contract and apply this figure to open interest at that level, then without considering price, collateral offsets, spread contracts, etc., the total margin requirement for all contracts would likely be only about $675 million.

However, if we focus on the 49,689 short silver contracts held by non-US banks on COMEX, as analyzed by "Tantu Macro":

Each contract represents 5,000 ounces, which, at $80 per ounce, corresponds to a nominal total of $20 billion. Under extreme assumptions—that these $20 billion in short positions originate entirely from a single bank and are held solely by the bank and not on behalf of clients—if the price of silver rises from $50 to $80 in the past month, the bank would incur losses amounting to approximately $7.5 billion. Adding to this the approximately $250 million in additional expenditure resulting from COMEX's two consecutive increases in silver margin requirements, the cumulative liquidity expenditure pressure in the extreme scenario reaches $7.75 billion.

Taking a major European bank as an example, as of the third quarter of 2025, it had approximately $330 billion in high-quality liquid assets, including approximately $230 billion in cash and approximately $70 billion in Tier 1 core capital. A liquidity expenditure of $7.75 billion would not be difficult, much less likely to trigger bankruptcy.

In fact, the conclusion is simple: with prices at unprecedented highs, the silver market doesn't need any mysterious bank collapses to become a mess. The publicly announced margin increases, extremely high implied volatility, and crowded trading are enough.

What's happening now isn't a story of bank liquidation; rather, it's a story of forced deleveraging. When silver prices start to surge, margin calls jump, prices plummet, and then someone posts a screenshot of "major banks going bankrupt overnight," many people's minds automatically go blank.

The idea of "crushing JPMorgan Chase and buying silver" isn't new. It seems plausible because it resonates with an old narrative, even though there's no visible empirical evidence to support it.

(Article source: CLS)